Warning of the ‘chilling effect’ sparked by Hong Kong’s security law

Exclusive: International scholars urge collective action against encroachment on academic freedom in China

This piece was published over three years ago.

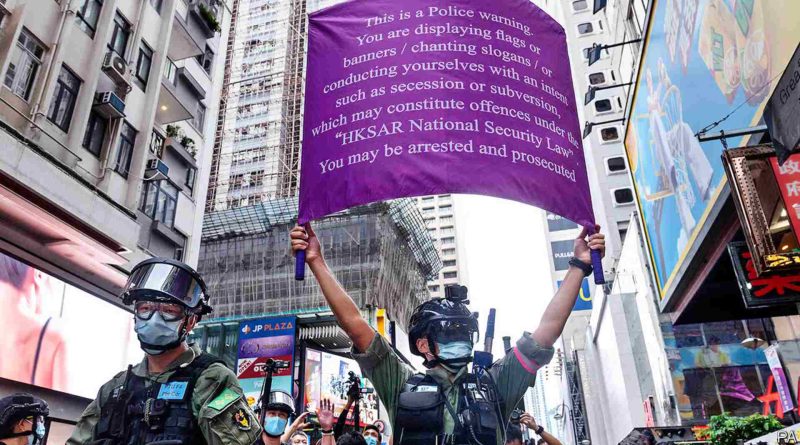

Concerns are mounting among academics regarding the impact of Hong Kong’s security law on academic freedom, with leading scholars calling for a unified global stance to protect university autonomy. They argue that Chinese authorities pose a growing threat to academic inquiry, particularly since the enactment of the national security law.

A coalition of 100 academics, hailing from the US, UK, Australia, and Germany, insists that without a concerted effort to combat Chinese state interference, individual universities will inevitably succumb to pressure. They specifically highlight the wide-reaching implications of article 38 of the security law, which extends its jurisdiction beyond Hong Kong’s borders.

Enacted by Beijing in response to pro-democracy protests, the law has sparked fears that students and scholars engaging in critical discourse on China could face severe repercussions, including lengthy imprisonment. Reports suggest that some universities are already witnessing self-censorship among students and faculty members, with China-related modules being dropped and academic writings toned down to avoid provoking the authorities.

In a joint statement, the signatories emphasize the fundamental role of universities as forums for open debate and critical inquiry. They condemn the security law for its global reach, warning that it undermines freedom of speech and academic independence, thereby stifling intellectual exchange and dissent.

Dr. Andreas Fulda, a senior fellow at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute and a key figure behind the initiative, underscores the need for collective action in defending academic freedoms. He highlights instances of students expressing concerns about potential repercussions for their comments or essays critical of the Chinese government.

Moreover, there are allegations that the Chinese government is leveraging students to monitor and report on their instructors, not only within China but also abroad. This pervasive climate of surveillance and intimidation extends beyond China’s borders, as illustrated by attempts to influence student demonstrations in Brussels.

Meanwhile, British academics are advocating for a code of conduct to govern university collaborations with foreign governments, emphasizing transparency and faculty consultation. They stress the importance of protecting foreign students and researchers from authoritarian regimes and ensuring the integrity of academic partnerships.

At Oxford University, Chinese professors are taking measures to anonymize student papers to alleviate fears of reprisals for critiquing the Chinese political system. This proactive approach reflects a broader concern about the potential consequences of academic engagement with China.

John Heathershaw, a professor of international relations at Exeter University, warns against the risks associated with universities relying on funding from authoritarian donors. He calls for greater transparency and faculty involvement in determining the terms of such collaborations to safeguard academic integrity.

In conclusion, the collective voices of scholars worldwide underscore the urgent need to defend academic freedom in the face of growing threats from authoritarian regimes. Only through solidarity and concerted action can universities uphold their essential role as bastions of free inquiry and intellectual exchange.