Featured Poem: “Brumby’s Run” by Banjo Paterson

In Banjo Paterson’s poignant ode to Australia’s untamed equines, a sense of wistfulness permeates the verses.

Brumby’s Run

Derived from Aboriginal language, “Brumby” designates a free-roaming steed. During a recent legal proceeding, a judge in New South Wales inquired, “Who is this Brumby, and where does his domain lie?”

It stretches past the silhouette of the Western Pines,

Toward the sun’s gentle descent,

And no surveyor’s mark delineates

The perimeters of “Brumby’s Run”.

On scraps of mountainous terrain,

Along trails of ridges and stone,

Where no others dare to stake their claim,

Old Brumby nurtures his herd.

An untamed, untamed bunch they are,

Of varied shapes and breeds.

Underneath the moon and stars they roam,

Venturing onto the plains to graze;

But as the dawn blushes the sky,

And creeps across the fields,

The Brumby horses turn and flee

Back toward the hills.

Travelers along the mountain paths

May catch the rhythm of their hoofbeats,

And glimpse shades of brown and black

Fleeting across the grass.

The eager stockhorse pricks its ears

And raises its head with anticipation,

In wild exhilaration upon hearing

The passage of the Brumby herd.

Old Brumby demands no payment or tribute

Across his vast expanse:

The one who corrals his herd is free

To retain them for their efforts.

Thus, they set off to scour the mountainside

With eager anticipation,

To the hiding places where the wild herds dwell

The gatherers venture forth.

A surge of horses through the foliage,

A flash of red shirts in action;

The crack of stockwhips on the wind,

As they disappear into the distance!

Alas! Before our days are spent,

We yearn with aching hearts

To once again ride upon Brumby’s Run

And corral his herd anew.

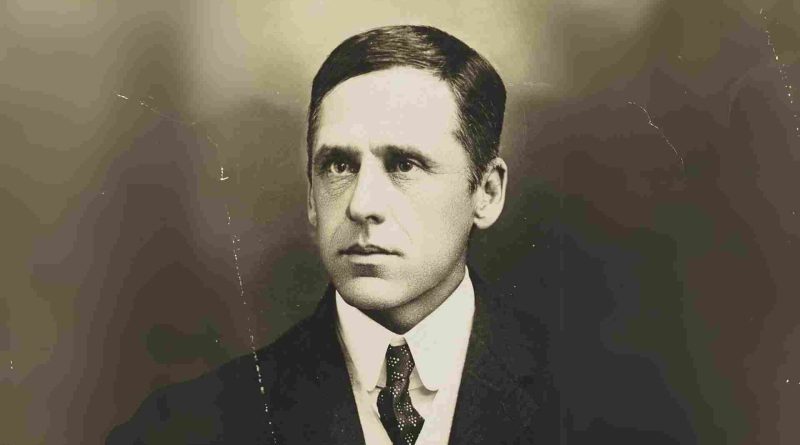

Andrew Barton Paterson (1864-1941), an Australian author and solicitor, often known as Banjo Paterson, is sometimes hailed as a poet of the outback. Descended from Scottish ancestry on his father’s side, he was born near Orange in New South Wales. Financial struggles necessitated the family’s relocation to Illalong Station, where Andrew, once old enough to ride a pony, attended the bush school in Binalong. Subsequently, he enrolled at Sydney Grammar School.

Paterson commenced his literary career in 1889, contributing to the Bulletin. Swiftly, he garnered a reputation as a poet and journalist. His fervor for horse riding and racing is evident in his chosen pseudonym: “The Banjo” was the name of his beloved racehorse.

His poems and ballads adhere to traditional metrics, meticulously crafted and enriched by the vernacular of outback settlers. Despite occasional stereotypical portrayals, his narratives, whether humorous, sentimental, or heroic, brim with the vitality of his firsthand experiences in the bush.

In the title of this week’s featured poem, “Run” denotes the territory frequented by animals – a place of roaming. However, the connotation of domestication is unmistakable: the “run” also signifies a pen for livestock. The horses depicted by Paterson are not truly wild, although unbranded; likely descendants of settler-owned horses that, escaping or being abandoned, have thrived to establish semi-feral populations. Paterson’s epigraph elucidates the potential origin of the term “brumby”. By personifying Brumby with a capital letter, Paterson elevates his status, casting him as a heroic figure who is also portrayed as the stockman’s neighbor. The second stanza masterfully situates him in his rugged domain, teasing us with his identity: “On odds and ends of mountain land, / On tracks of range and rock / Where no one else can make a stand, / Old Brumby rears his stock.”

Apart from this, there’s minimal anthropomorphism in the poem. Its descriptive language is delicately applied. The elusive hoofbeats are captured in alternating tetrameter/trimeter rhythms; when the horses are sighted, they are described only briefly as “a glimpse of black and brown”. In the first stanza, the horses’ “run” is depicted devoid of human intervention and exploitation, yet there’s a hint of decline; despite its seemingly boundless expanses, the terrain appears to fade into the sunset.

The narrator and his eager mount seem to be “gully rakers”, eager to chase down and capture “the Brumby mob”. The closing lines carry a nostalgic tone, candidly acknowledging the nature of their longing: “Ah, me! before our day is done / We long with bitter pain / To ride once more on Brumby’s Run / And corral his herd anew.” While the horses are admired and even revered, their primary function is to be pursued – potential livestock whose capture provides thrilling sport.